What Does a Just Society Actually Look Like?

Balancing individualism & collectivism to build a world of equal opportunity

What, if anything, does society owe people? How do you determine what is fair? What does justice mean? These seemingly abstract questions have assumed great urgency in our tumultuous times. The public discourse is full of outcry against numerous injustices— economic, racial, gender, climate, and more. The result is a society divided across numerous fault lines.

Nowhere are these fault lines more visible than the murder of Brian Thompson, the CEO of United Healthcare, by alleged perpetrator Luigi Mangione. Many see Mangione’s act as murder. Others, outraged by economic injustice, believe it was a desperate act against a corrupt system. But how do you determine whether people are justified in their grievances? And if they are, how do we design a society that addresses those grievances? These questions are the focus of this essay, which is part 3 in a series of 7 essays examining the killing.

In part 2 of this series, we saw how morality’s subjectivity limited it in helping us resolve these kinds of differences. Luckily for us, philosopher John Rawls came up with an ingenious thought experiment to help us understand the nature of justice. Enter the Veil of Ignorance.

The Veil of Ignorance

Imagine that you are tasked with designing a society- its laws, rules, culture, norms, education, and economic systems– anything and everything you see around you that makes up our lives. The only catch—you do not know your race, gender, place of birth, intelligence, health, looks—nothing. If it helps, think of yourself as a soul waiting to be born and you have no idea of what your lot would be. You could be a Wall Street banker’s son or someone racially discriminated against. A powerful politician or someone who will be denied healthcare. Now ask yourself—what kind of a world would you want to be born into?

The brilliance of the experiment lies in helping us move past our biases towards ourselves and our in-group. It does so by hiding from us those factors that are purely determined by luck. It also exposes a blindspot in arguments for meritocracy. It shows us that we are all born in different circumstances and these random accidents of birth play more of a role in our successes and others' failures than we like to admit. If one imagines life to be a race, then it is clear that not everyone has the same starting line. It is worth indulging in the thought experiment yourself to see what societal principles you would come up with after realizing the role of luck in life outcomes.

Rawls posited that most people would come up with the following principles:

Equal basic liberties for all (fundamental rights like free speech, voting, etc.)

Social and economic inequalities are only okay if:

There is equal opportunity for everyone to achieve those outcomes

The existence of inequality benefits even the most disadvantaged members of society. He called this confusing-sounding maxim the difference principle. We will revisit it later in the essay to elaborate on what it means

The reason Rawls says we will come up with these principles is because if we don’t know our position, we would want to ensure that even the worst-off people have good life outcomes. The first principle is fairly uncontroversial and is reflected in laws and rights across most of the world. It is the second that gets to the heart of the current divide between the haves and have-nots.

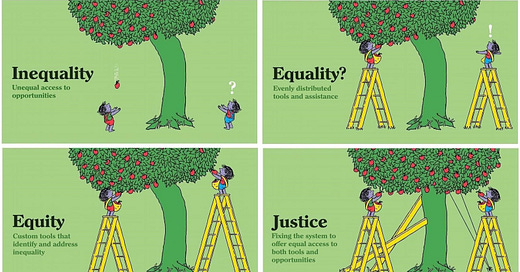

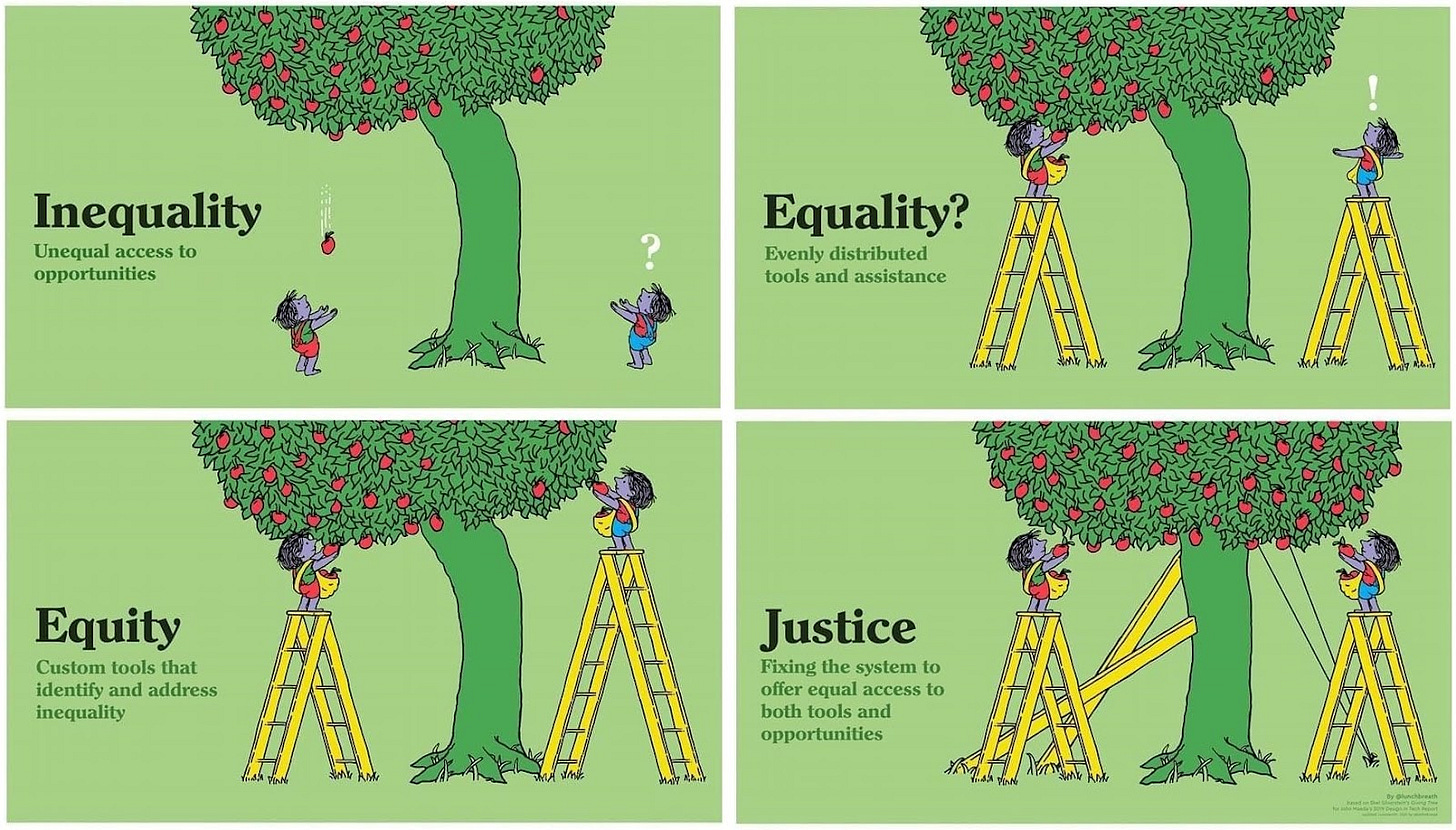

It is important to note that Rawls does not say that we shouldn’t have inequality. In point 2a, he is only saying that everyone should have an equal opportunity to achieve those outcomes. This is essential if we are to have a stable and just society. This too seems like it should be a fairly uncontroversial idea on the surface. But the devil, as always, lies in the details. The following image helps illustrate the link between luck, equality of opportunity, and justice that Rawls is talking about. Let’s analyze it from the lens of access to education.

Equality, equity or justice?

The first scenario is one of inequality where the tree is highly tilted and laden with fruits on one side. The child on the left gets more fruits purely by the accident of being in that position. This can be equated to a child born into a rich family being able to afford a private school while a child born into a poor family goes to public school. This is the role of luck and our bias because of it that Rawls wanted to remove through the veil.

In scenario 2, equality says give every student a $5,000 scholarship regardless of background. In scenario 3, equity asks: does a poor student need more to catch up? If one child has generational wealth and tutors while another struggles for basics, then the scholarship amount should reflect the poorer student’s need. This would meet Rawls’ test of equality of opportunity. However, this isn’t ideal because it requires an ongoing compensatory mechanism.

In the final scenario, societal barriers are addressed and the student’s family is uplifted from poverty or public schooling outcomes are on par with private schooling– we have true justice because everyone is on a level playing field.

If these corrections seem like overkill- I ask you to revisit the thought experiment. From behind the veil of ignorance, not knowing whether you would be the child on the left or the right- what world would you design?

Please note that this is not about ensuring equality of outcome. Each child must still pluck the fruits themselves. Their outcomes will still be determined by the work they put in. This is just ensuring that both children have the same chance of being able to get the fruit. Social justice is of course not a popular term in the USA these days, with the widespread repealing of Diversity Equity and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives across the country. A lot of pushback against these policies comes from misunderstanding their intent, different interpretations of ideas of meritocracy, social justice, and equal opportunities coupled with biased perspectives.

To the child on the left, the change from scenario 1 of inequality to scenario 3 of equity will seem like the system is working against him and that the child on the right is getting special treatment. This will especially be the case if you as the child on the left already aren’t experiencing a great quality of life. While 3 billionaires hold as much wealth as the bottom 50% of Americans– the majority of the people are grappling with high costs of living and staring at a future where they are worse off than their parent’s generation. Unfortunately, instead of using these facts as motivation to fix systemic problems, politicians have spun a narrative that things like DEI and unchecked immigration are the cause of people’s dwindling prospects. This offers easy scapegoats and avoids responsibility for tackling the much harder question of economic system reform.

But politicians will play whatever games they need to gain power. We should focus on making a concerted effort to reach scenario 4 to avoid the resentment generated by ongoing interventions in scenario 3. This is not a utopian ideal. Many countries have made justice an on-ground reality. 80% of Singapore’s population lives in affordable government housing. Finland’s public education system ranks as the best in the world and provides equal opportunities to all students regardless of their background.

The difference principle and caveats

Having established how luck and opportunity intertwine, let’s see how Rawls extends his framework for justice with his difference principle—inequalities are only okay if they benefit the most disadvantaged members of society. Here, Rawls is recognizing that some forms of inequality are actually good for society because unequal outcomes serve as an incentive for people to innovate or work harder—which leads to gains for the whole society. Let’s look at a world where a doctor is paid half a million dollars while the median income is 60000 dollars. Here, not paying half a million to the doctor actually results in worse outcomes for the average person. How could that be? Imagine a case where even doctors are paid 60000 dollars. In this scenario—nobody would have the incentive to put in the tremendous hard work needed to become a doctor and as a result, we would have no healthcare and everybody would have a shorter disease-laden life. This is an important principle to keep in mind so that in a zealousness to correct systemic injustices, we don’t end up creating a lose-lose by chasing equality of outcomes.

Okay, so far, so good. Most people would not object to a doctor being paid more to do harder work. But making better outcomes for everyone a necessary condition for inequality is where it gets tricky. I would much rather give everyone a level playing field and then let people have the outcomes they may, instead of introducing such caveats. Many free-market economists object to it as well. Especially, since the principle, in application, leads to wealth redistribution policies like progressive taxation and inheritance tax. This is viewed by some as forced charity. Another potential objection is that of free-loading. The late philosopher Robert Nozick said that the difference principle makes it so that someone not working hard can feel entitled to benefit from the labor of someone who is.

Is there a way to reconcile these differences and find some justification for the necessary condition of improving the lot of everyone in the difference principle? Just like most people, I dislike high taxes, so I initially struggled to endorse things like progressive taxation and inheritance taxes. But I think there is an enlightened self-interest case to be made for them and the difference principle. So indulge me, if you will, in a few more thought experiments.

Empathy for the rich?

Counter-intuitive as the sub-heading above might sound, a truly just society is just to everyone and not only to those in need. So let’s begin by applying Rawls’s veil of ignorance from the perspective of the rich person. Imagine for a second that you have an income of 100 million dollars per year. Let’s assume you optimize taxes and end up paying an effective tax rate of 20% for a total of 20 million dollars in taxes. In contrast, someone earning 50000 dollars per year in Toronto would pay about 12000 dollars in taxes—an effective tax rate of 24%. This scenario is not far-fetched, Warren Buffett famously said that he pays a lower tax rate than his secretary as most of his income comes from capital gains which are taxed at a lower rate.

Now, someone earning 100 million dollars paying a lesser tax rate than someone earning 50000 dollars causes a lot of outrage among people. But my question is—why should it? In absolute terms, you are still paying 20 million dollars vs the 12000 paid by the lower-earning person. Arguments I found online try to justify it by couching it in terms that the rich folks avail a higher share of public services like business laws, intellectual property protection, etc so they should pay more. But can we really quantify it and prove that the services they availed are worth 20 million dollars? We would probably be hard-pressed to do so just in terms of the costs of these services. In the end, the argument comes down to the fact that we as a society need certain services and some people are just more able to pay for them. But doing it through a higher tax rate vs charity can be seen as a form of coercion—an idea many economists are against.

Likewise, the problem of freeloading raised by Robert Nozick is real. As much as we want to build a welfare society, in the end, we all have to pull our own weight, and welfare mechanisms need to be designed in a way that helps people become independent. Else, they become ripe for exploitation by populist governments who give handouts before elections, all the while dismantling systems that would enable people to become educated and independent. That is a true subversion of justice. The inefficiency and corruption in governments is real. If rich people believe that their tax dollars are being put to good use then more would be willing to pay their ‘fair’ share. Sweden, for instance, not only makes budget documents publicly available—it also publishes detailed reports linking spending to measurable outcomes. Other countries need to develop similar robust accountability and transparency mechanisms to make government data more accessible to the general public.

In addition to dealing with the above challenges, it is imperative that we stop demonizing all rich folks. If you, as someone paying 20 million dollars in taxes, find yourself surrounded by the “Eat the rich” narratives floating around today—how would you feel? It is critical to remember that while bad actors and corrupt individuals certainly exist, many rich people have earned their wealth through hard work, grit, and agency. They became wealthy because they created wealth for society and under the norms of society retained a portion of it for themselves. Wealth creation, when not subverted by corruption, is a positive sum game. As such, unpopular as this take might be, we need to recognize the contribution of the wealth creators. If the notion of empathy for the rich seems absurd, it's worth remembering that many of us—often unintentionally—benefit from broader systems of inequality and exploitation, such as disparities between the global north and south. Recognizing this complexity can help us approach these issues with humility and fairness.

Some people contribute disproportionately to the progress of society and if we want them to pay higher taxes, then the way to do that is not by making them the enemy and demanding they pay more. Instead, we can learn some lessons from Scandinavian countries that foster community spirit and make payment of high taxes a marker of high status. Additionally, instead of painting an ‘us vs them’ narrative, we can show rich folks that these taxes actually serve their self-interest too. Let’s see how we can do that.

A little support goes a long way. If you find this post useful, please consider a small contribution to keep this going

The enlightened self-interest case for progressive taxation

First, we need to recognize that living in a society and adhering to its norms is a cooperative game we have agreed to play together. We, as individuals, agree to abstain from violence as long as we believe this system will take care of us. Under this system, it is only the government that is allowed to use force to enforce laws or maintain peace. This is the social contract that makes society stable in the long run.

Second, we need to go back to Rawls’s idea that luck means we all have a different starting line. Progressive taxation is needed so we can address historic inequities and get everyone on the same starting line. This is not a one-time effort. Even if we give everyone in one generation a level playing field, some redistribution would be needed in the next generation. This is because due to the role of luck or effort, people will have unequal outcomes even when starting from the same place. To maintain societal stability over the long run, it is necessary that these unequal outcomes don’t compound to a glaring power difference over the long run. Because if they do, someone facing persistent inequality and diminished life outcomes has no incentive to play by the rules and might try to resort to violence or break the system. This is partly what happened in the case of Luigi. It is also what led to the collapse of many historical civilizations—the fall of the Roman Empire and the French Revolution are notable examples. This shows why redistribution actually makes sense from the perspective of self-preservation.

However, the threat of violence makes this too a form of coercion and I am not very happy about that. Luckily, it is not just loss aversion that makes redistribution sensible—there is also a positive upside. Research indicates that, although happiness generally increases with income, the magnitude of this increase is surprisingly small. In fact, the happiness gained from significantly higher income levels is comparable to everyday effects—such as the difference in happiness from weekdays to weekends. In which case, you can actually do better for yourself by giving your wealth away. How so? If you fund education or research—someone can invent something that you might benefit from—like a life-saving drug. If you fund a public park or sponsor homeless shelters then your neighbourhood is nicer and safer and you are hailed as a pillar of society.

Additionally, if wealth is more widely distributed in society then it leads to higher economic consumption. This kicks off a virtuous cycle that benefits the wealthy because most of their wealth either comes from owning businesses or having equity investments—both of which benefit from higher economic activity—a true win-win.

The enlightened self-interest case for inheritance taxes

Assuming the arguments above persuade you of the need for progressive taxation, you might still balk at the idea of paying inheritance taxes on top of that. How much of the reduction of this inequality is our burden to bear after all? Probably higher than we think or like. Imagine you are the head, the alpha, of a pride of lions. Through your strength, you command the highest share of meat and the best choice of mate. But eventually, you grow old or weak and someone challenges you for leadership of the pride. If they defeat you, then all the spoils that were yours now belong to them. They do not go to your offspring. That is, in the animal kingdom your advantages (apart from your genetics) are not passed on to your child.

This is not the case with humans. Through the invention of money, private property, and inheritance laws we have made it possible to pass on any advantages we have to future generations. As noted in the case of progressive taxation above—this leads to a compounding difference in power and subsequent societal instability. With this perspective, the right question to ask is not why one should pay inheritance taxes but why should one be allowed to pass on anything to one’s offspring at all.

Reconciling individualism and collectivism: Justice in a divided age

The thought experiments above show that the line between collectivism and individualism is tough to draw, but it can’t be at either extreme. We must find a balance between ‘The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must’ and the maxim of Ubuntu—‘I am because we are’. The difference principle seems to carry a whiff of communism when first looked at. A finer examination shows why it is essential but needs to be applied alongside other mechanisms that recognize individual contributions. As people on either side of the divide of haves and have-nots, we must be careful not to cut down the very tree whose branches we sit on.

As any one individual, some parts of this bargain might feel unfair—but we would do well to remember that we are able to thrive only because society thrives. All our achievements are built on top of the achievements of countless people who came before us. If there is no justice, no equality of opportunity—then there is no society—we have no legs to stand on.

Rawls shows us how we can design a just society that addresses the grievances Luigi represents. The veil of ignorance sidesteps the challenges of moralizing that are prevalent in our discourse today and shows us that ensuring a harmonious co-existence requires us to build a world of equal opportunity. In my next essay, I will share data from housing, education, and healthcare to show that we are far from achieving this ideal. The ladder of opportunity that Rawls advocates for is rapidly slipping out of reach of the vast majority. 100 million Americans are reeling under the debt burdens of health care. Most can never afford to buy a home. These aren’t just ‘inequities’—they are failures of justice that present a very real threat to societal stability. Luigi’s actions show that when people are denied justice they seek it in desperate ways. We can no longer hide behind the illusion of fairness. If we are to counter the threat of ever-escalating violence—we must increase transparency in government spending, abandon divisive ‘us vs them’ narratives, reshape taxation as a form of civic pride, and design government programs that empower rather than create dependence. The stakes are high, and the responsibility belongs to us all.

Alternatively, if you find this post useful, please consider a small contribution to keep this going

Thank you for the post. I am following this series closely, and would like to offer my criticisms:

You advocate a Rawlsian process of deciding on shared principles from a veil of ignorance, and you call this “true morality.” But this seems to contradict your position that morality is fiction, that it can only be justified by how useful it is. Rawls’ notion of justice should be no exception. Will this notion actually be most useful, and lead to the greatest human flourishing? Maybe, but that is hardly something that can be ascertained from behind the veil, unless, paradoxically, one first prejudicially assumes that all prejudiced moral theories are false (the most prevalent of which, such as religious creeds, also typically claim to be the most beneficial for all individuals and communities regardless of their circumstances). And in fact, this is what you seem to be doing - rejecting all other moral theories as fictions despite this being ostensibly impossible from behind the veil. I believe what you are really arguing for in this series, in effect, is not that morality is fiction, or that one needs to deliberate about it from behind a veil of ignorance; but that it is very real, that it conforms to the Rawlsian system, and that it draws its justification from its conduciveness to good individual and collective consequences (which you seem to emphasize as being primarily material/economic). This seems rather like consequentialism (with some special egalitarian / redistributive parameters), a position which postulates objective moral truth and requires no veil of ignorance to conceive and define. Personally, I agree with the gist of what you say about preventing rampant inequality, needing to have some reliable form of wealth redistribution, needing to reconcile people to seeing their individual interests reflected in the community’s interest, etc. But, problems with consequentialism aside, none of this seems to depend on assuming morality is fiction or that the Rawlsian solution is itself anything other than its own kind of moral prejudice. Simply by claiming morality is fiction and then claiming there are better or worse or more or less useful fictions, you effectively reproduce a claim to objective moral truth, and this kind of claim is always prejudicial.

A very thought provoking article re-emphasising the principles of Ubuntu. In a world that often values individual gain, Ubuntu tries to give recognition to our interconnectedness and shared fate.

Such a noble concept struggles to achieve it's full potential due to a plethora of reasons.

Main amongst these are culture erosion, rapid urbanisation, economic pressures and it's being in direct conflict with those in power who want to cling to it. These principals have not found support or failed to integrate with education and politics.

The article is entirely readable and stands out for its clarity.