Beyond Good And Evil: The Limitations of Morality

Why Absolute Moral Judgments Fail Us—and What Works Instead

Do good and evil exist? How do we determine what is right and wrong? Considering how a controversial tweet or a viral incident can polarize communities overnight—what does that reveal about our collective ability to answer these questions? Right as determined by who? On what parameter? These are some of the treacherous questions one runs into if one spends any amount of time thinking about morality. Grappling with them, one quickly realizes that many beliefs one holds dear are on shaky ground. But despite this, the world today is awash in moral judgments.

One need not look far—the killing of Brian Thompson, the CEO of United Healthcare Insurance, by Luigi Mangione (alleged perpetrator, awaiting hearing) has exposed the fault lines in the debate around morality. The Luigi Mangione case has as its backdrop a society with massive inequality. Some people, like Senator Bernie Sanders, decry that 3 billionaires holding as much wealth as the bottom 50% of Americans is immoral. Many of them condone the killing. Outraged by economic injustice, they believe it was a desperate act against a corrupt system.

Others see Mangione’s act as murder. They accuse Mangione’s supporters of hypocrisy and losing their moral compass. They are aghast at how people who claim to be champions of social justice and equity are supporting murder. But if we can’t even agree on whether killing someone is moral or monstrous, what does that say about morality itself?

This essay, part 2 of a 7-part series examining the killing, studies the moral divide to see if there is a way to bridge it. This can help ensure that the killing acts as a catalyst for systems change rather than further division. In this essay, I argue that morality, while a useful fiction, is subjective and its misuse often hinders meaningful societal progress by fostering division and judgment. Morality is society’s evolving and subjective framework of norms and values. But people often weaponize it through moralizing—by imposing personal values onto others. That’s a big part of what has happened in this case. It has allowed people to operate in the arena of reactive moral outrage rather than proactive problem-solving.

How moral judgments foster division

People on both sides of the Luigi debate believe they are morally correct. The anti-Luigi side might agree that inequality is bad but insist that murder is never justified—Luigi should have worked within the system. The pro-Luigi side might argue that the system itself is broken—he was stonewalled, desperate, and had no real choice. How do you resolve this moral deadlock?

The situation is not helped by social media as online debates are mostly reduced to some version of “Rich man bad”, “Poor man lazy” etc. Why does this happen? It’s because people instead of using morality as a guide to ethical thinking, misuse it as a cudgel to silence dissent. When individuals conflate their subjective interpretations with universal truth, dialogue collapses. Couple this with the fact that casting moral judgment on others can help us feel superior and give us a dopamine kick, and amplify it a millionfold through social media, and you have the fractured society of today. This fracture is all too palpable in the case of Luigi Mangione and Brian Thompson. Instead of focusing on nuance, we are splintering into tribes, with the only relevant question being— “Whose side are you on?”

The graph below from Pew Research is old, but it shows how polarization has been increasing in the US. The share of Americans holding a mix of conservative and liberal positions decreased from 50% in 2004 to 33% in 2017. Given how American politics has played out since, there is no reason to believe this has gotten better.

This rising polarization underscores how moral judgments, far from inviting dialogue, can deepen rifts in a pluralistic society—particularly when each side believes its own moral code is universal.

The pluralistic nature of society

If we are to make progress in designing a better world, it is imperative to suspend moral judgments and reverse the trends this graph shows to come together. But how should we do so? We all hold our moral convictions pretty deeply after all.

The key, I think, is recognizing that no moral truth is absolute, but instead all are driven by personal and cultural contexts. People on each side of the divide judge the other based on their own norms, because they think we live in one society and share a single moral framework. But we actually live in a stitched-together tapestry of many, many sub-societies and cultures– each with its beliefs, norms, and taboos. This means we operate under different value systems. This means that someone not subscribing to our set of values is not wrong, they are just different. Accepting these differences is key to living together in a pluralistic society. Those who refuse to accept these differences and try to impose their world view on others are not indulging in morality, but the powerplay of self-righteousness.

Now, I don’t expect you to take me on face value when I say morality is subjective. Below I present some slightly extreme examples to demonstrate the point. I hope that they can help people on both sides of the divide see the ‘other side’ as slightly less evil or stupid.

The subjectivity of morality

Let’s think about the act of murder, outside of Luigi Mangione’s case. Most people would consider it to be an immoral act—with few exceptions. But the morality becomes fuzzier when we consider how we treat other species.

What if I told you that to be truly compassionate and moral—you not only have to become vegetarian, you also have to avoid root vegetables like potatoes, whose harvesting would lead to the death of the whole plant and potentially the microbes in the soil? That you must never walk on grass to avoid killing insects and even wear masks so you don’t unwittingly inhale and kill some microscopic organisms.

Sounds pretty extreme, right? In this example, it seems empathy and morality have been taken far enough to make existence a crime. But I did not make this example up. This is precisely the moral framework of the Jain religion in India, which teaches reverence for all life. To a Jain, our indifference to insect lives might be as immoral as their potato avoidance is absurd to us. But neither is ‘right’—both are cultural choices

This example shows that moral boundaries shift depending on the lens we use. People have different justifications for where the line is drawn. The Jains believe everything has a soul. Some people say animals can experience pain, but plants can’t—so it is okay to kill plants. Some find justification in relative levels of consciousness or complexity of the nervous system. However, it is important to realize that these criteria too are just reflections of the subjective personal and cultural values.

But if potato ethics seem absurd, let’s take another example. This one is from researcher Jonathan Haidt who has studied the link between morality and disgust to show that moral judgments aren’t necessarily rationally deduced but arise directly from feelings of pleasure or displeasure. It might seem extreme <TRIGGER WARNING> and make some readers uncomfortable, but I include it to show that even deep-seated moral intuitions that feel self-evident, and beyond question might not be shared by everyone.

Jonathan Haidt asks whether a consensual, one-time sexual encounter between adult siblings is morally wrong if it causes no harm to anyone. In this thought experiment, the siblings use contraception, decide to keep the act a secret, and never repeat it.

Haidt uses this extreme scenario not to normalize incest, but to expose that moral disgust often overrides logic. Even when all consideration of harm– genetic, family harmony or societal discord are removed, our instincts continue to tell us something is wrong. But is that instinct truly pointing towards inherent, inviolable morality, or just conditioning?

Evidence from some social experiments and practices in some cultures suggest that the reaction is conditioned. You might be surprised to hear that incest is actually legal in 74 countries, including France, Italy and the Netherlands. Cousin-marriage, that is similarly taboo in most cultures, is actually legal in 19 US states. In fact, many famous historical figures, like Queen Victoria, Charles Darwin and Albert Einstein, married their first cousins. These numerous examples demonstrate how moral boundaries are deeply shaped by cultural context and highlight the arbitrariness of where we draw the line.

To complicate matters further—morality not only varies by culture, it also evolves with time. One only needs to look at the fact that homosexuality was once considered immoral and that people had the gall to make moral arguments in favour of slavery to know this is the case. In the case of slavery, arguments ranged from it being divinely ordained to slavery being a benevolent act as it rescued slaves from a life of “barbarism. An ingenious argument even compared slavery favorably to the wage labor system in the industrialized North. It claimed that enslaved people were cared for throughout their lives, whereas wage laborers were exploited and discarded when no longer useful. This shows that morality can be weaponized to justify self-serving ends based on societal norms.

I hope these examples, though extreme, convince you that labeling people as "wrong" or "evil" often reflects societal discomfort with actions that deviate from the norm, rather than an objective assessment of harm or intent. It is clear that people are divided by conflicting moral frameworks in the case of Luigi and Brian. Fairness, justice, and equality on one side. Individual responsibility, the rule of law, and meritocracy on the other. Moralizing has created a false binary (good vs. evil) that prevents nuanced debate. The problem isn’t just that people disagree—it’s that they believe their moral framework is universally correct, leaving no room for reconciliation. When we mistake our moral compass for a universal GPS, we stop navigating and start colliding.

A little support goes a long way. If you find this post useful, please consider a small contribution to keep this inquiry going

How Morality Can Be Used For Good

Now that we have established the subjectivity of all morality—does that mean we should discard it altogether? If the lines we draw are truly subjective, then what’s to stop someone from saying it’s not immoral to kill other human beings? Are actions like theft and murder both equally moral/immoral? Not necessarily. As my wife pointed out to me, even if all morality is subjective—it doesn’t mean it is not useful. Moral standards and moral language prevent our society from descending into total chaos and promote a harmonious co-existence. So morality is a useful shared fiction. And it can be a great driver of change. Moral frameworks, when leveraged inclusively rather than divisively, can unify us around shared principles.

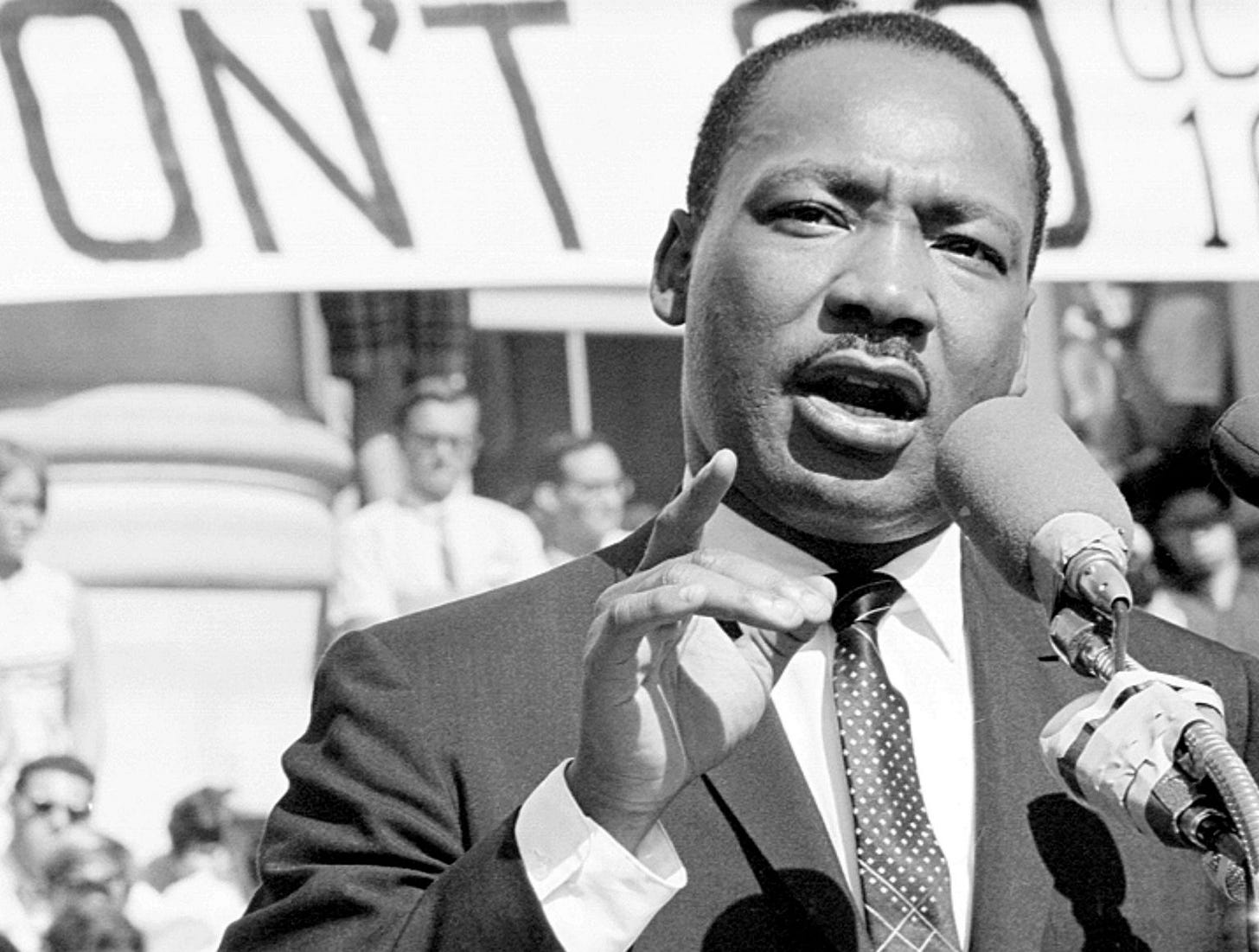

A great example of how to weild morality effectively for good is the Civil Rights Movement in the US that led to the end of segregation and discrimination against Blacks. It did so not by moralizing, but by exposing inconsistencies and hypocrisy in the existing moral framework. The US had fought in the World War to preserve freedom, all the while denying freedom and equal treatment to the Black population at home.

Martin Luther King in his famous “I have a dream” speech emphasized an inclusive vision rooted in ideas shared by both Black and White Americans: “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’” This approach avoided creating an “us vs. them” narrative. Instead, it invited people—especially white Americans—to see themselves as part of a shared moral struggle. Unlike today’s ‘eat the rich’ slogans, the movement expanded its moral circle—inviting elites to join, not vilify. And plenty of white people responded, some even losing their lives in support of the movement.

The movement also committed to nonviolence, both as a moral stance and a strategic choice. Leaders encouraged activists to respond to hatred and violence with dignity, restraint, and love, turning the moral spotlight on the injustice of their oppressors. The Selma marches and sit-ins vividly illustrated the stark contrast between peaceful protesters and violent enforcers of segregation, making it clear who held the moral high ground.

The Civil Rights Movement contains many lessons for how we can approach the Luigi Mangione situation. The movement demonstrated that a shared morality builds bridges while moralizing burns them. How do we put the lessons from the movement into practice and find a shared vision for a better world? By doing the following:

Letting go of the notion that our moral truth is absolute and people with different values are immoral

Realizing that we carry unconscious biases based on our circumstances, culture, and life experiences.

Recognizing that moralizing and shaming people is only going to put them on the defensive and probably entrench them further in their position

Not painting groups of people with broad brushstrokes. “The down with the rich” narrative alienates potential allies among the rich who want to pursue social change. Many of them have worked hard for what they have. And the hostile environment is going to drive them toward self-preservation rather than driving societal change

Get offline and talk to people in real life. Social media platforms reduce morality to dunk contests. But unlike on social media, offline we find even people holding completely opposite opinions to be reasonable. Join a citizens’ assembly. Attend a town hall. Debate in spaces where nuance survives

Realizing that we are all hypocrites to an extent. Many of the goods we consume– lithium from mines in Congo, fast fashion, etc are products of questionable labour practices. Apple, for instance, was accused of relying on conflict minerals by the government of Congo in 2024. Many of the issues we face are systemic and not rooted in the moral failings of individuals. If we want real change, we must stop punishing individuals for participating in flawed systems and start focusing on reforming the systems themselves.

The world is not lacking in simplistic moral judgments. What we lack is the courage and willingness to listen, to replace outrage with curiosity. The world is complex and there aren’t easy solutions to many of our challenges. In the next essay, I discuss how we can embrace this complexity and try to design a just society despite our moral differences. By rejecting moral rigidity, we can construct a society where justice is not dictated by dogmas but is the result of thoughtful, inclusive dialogue. The killing of Brian Thompson shows that we can ill-afford to continue the status quo, but moralizing is not going to help us move ahead. A society trapped in moral absolutes can’t fix real injustices—it can only deepen them. Morality can be a weapon to divide, or a loom to weave us together. The choice isn’t abstract—it’s ours, and it starts with how we listen, debate, and act today.

Alternatively, if you find this post useful, please consider a small contribution to keep this inquiry going. A little support goes a long way

Very thought provoking. You make some very valid points. Look forward to going through the next article in this series.

Love the articulation, esp. point #6. Great article as always Akhil.