Metacrisis: The root of all our planetary crises

What Climate change, AI risk, the mental health epidemic & more have in common

There is a crisis afoot. It isn’t one you usually hear about in the news, and there are of course plenty of those. What if I told you that seemingly different problems like climate change, war, nuclear and AI risk, the mental health epidemic, and indeed most of our planetary crises stem from a common root cause? That, as large as all the above crises are, they are just symptoms of something larger? That Greenland and Antacrtica losing 400 billion tons of ice every year, a billion people living with a mental disorder, unchecked AI threatening human extinction, and microplastics constituting .5% of our brain by weight are all signs of a deeper systemic crisis? Then maybe, just maybe, we might have a shot at solving them. That’s the thesis this essay presents— that there is a crisis hiding beneath all our crises— The Metacrisis.

If any of the crises mentioned above has ever had you wondering why the world seems to be coming apart and why we seem to be unable to do anything about it, then you have already touched the boundaries of the Metacrisis. Since a full understanding of what the Metacrisis points at is complex, I am going to begin with a high-level definition and then add nuance as we go along.

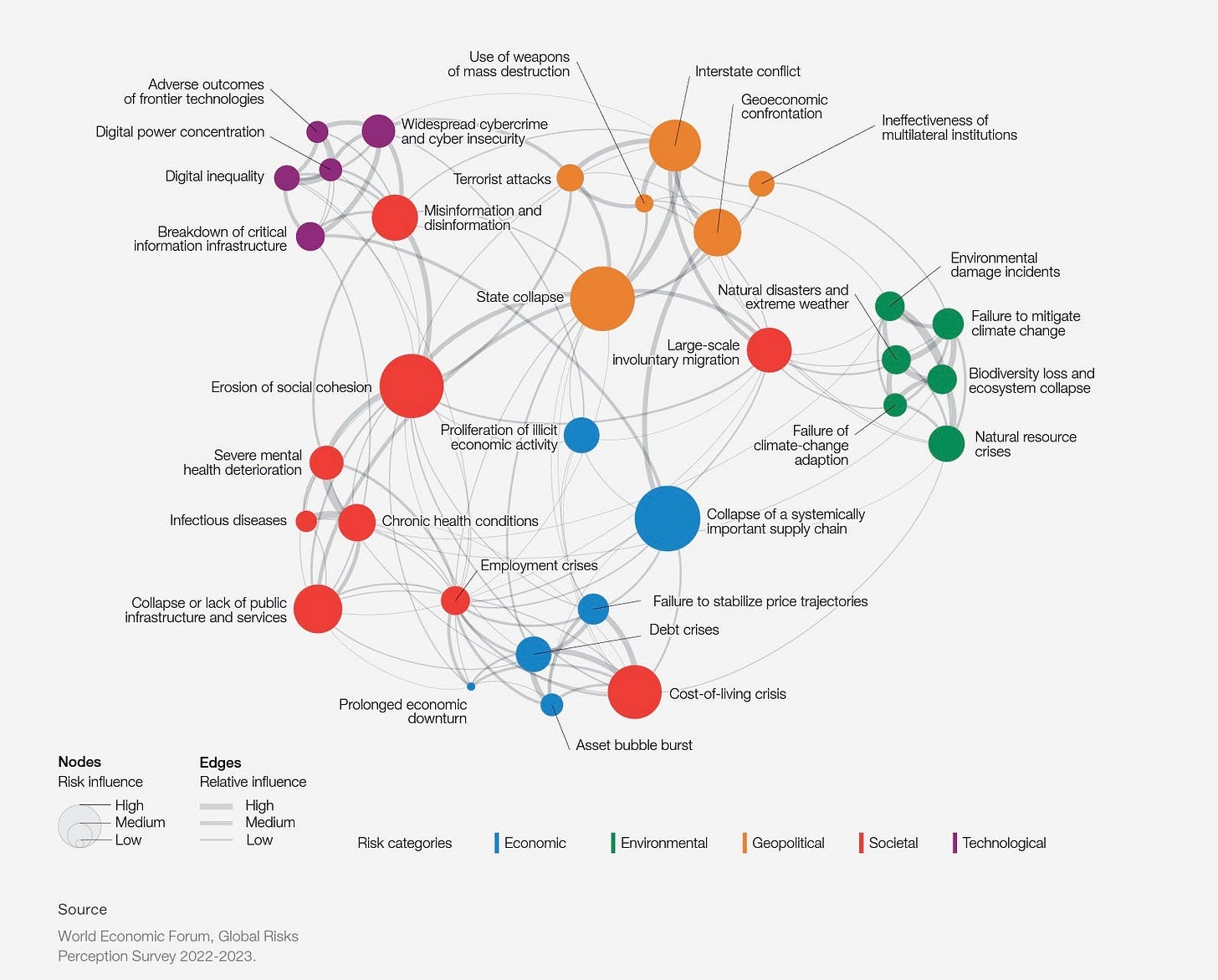

At its simplest, Metacrisis refers to the fact that the massive existential risks we face today are:

Systemic i.e. they arise from the nature of our political, economic & societal structures and incentives like short-term profit maximization

Interconnected and mutually reinforcing i.e. one issue makes others worse and harder to solve. For example, fake news leads to climate denial which makes it harder to solve climate change. Climate change leads to natural disasters and increased inequality, which lead to increased migration, which leads to increased Xenophobia, which leads to more fake news

Deep rooted in human nature i.e. our pursuit of power and status and our tendency to think short-term and non-holistically.

It is helpful to think of the Metacrisis as akin to a Hydra, a multi-headed monster in Greek mythology that grew two new heads whenever one of its heads was chopped off. Though each of our planetary crises has unique contributing factors, they are all in many ways one of the heads of this Hydra. This means that the challenges we face today can’t be solved by our existing systems and institutions or indeed even our current way of life. Addressing the root of our existential malaise needs a fundamental transformation in our culture, education, government, markets, values, and more. Without systemic changes, individual solutions will be just like cutting one of the heads of the Hydra— a futile effort, soon rendered in vain by new problems popping up. I write this essay with the hope that by understanding the nature of the Metacrisis hydra accurately, we can be victorious in our efforts to slay it.

While the rest of the essay will go into more detail, some illustrative changes include moving away from an economic system narrowly focused on short-term economic growth, political funding reforms and shifting cultural narratives from a focus on wealth accumulation to holistic well-being. I know those sound like big claims, but I will attempt to substantiate them by sharing with you my own doubt-ridden journey to these conclusions. Much of what I will share below will be through the lens of the climate crisis, as that was the first manifestation of the Metacrisis that I encountered. However, I will demonstrate that the same patterns that lie at the core of the climate crisis define our other crises as well.

Down the rabbit hole

My journey began in 2016 in Bangalore, India’s Silicon Valley, a city I had called home for half my life. Bangalore was then commonly known as the ‘Garden City of India’ because of its famously cool climate that drew tech immigrants and retirees to the city alike. So I was extremely alarmed when the summer brought with it a record-breaking heatwave and scenes right out of hell— lakes catching on fire due to pollution. Seeing my home transform from a garden to a hellscape before my eyes, sent me down the rabbit hole of understanding the environmental catastrophe unfolding across our planet. What I learned convinced me that unless we changed trajectory on climate change dramatically, we were surely headed for disaster as a species. It was not a reality I wished to reckon with and my mind assessed many escapist tactics to avoid the problem— would I be okay if I became a multi-millionaire, would I be okay if I had political power, would I be okay if I moved to another country? On and on, I tried negotiating with reality until the only conclusion I was left with was that there was no escape and this problem had to be tackled head-on.

A trip to the Himalayas with a friend later in the year filled me with great sorrow as we sat nestled in the foothills of the majestic snowcapped mountains. “All this will be lost”, discussed my friend and I almost every day of that trip. That sorrow galvanized my motivation to work on climate change and filled me with a sense of purpose. Subsequently, in August 2017, I left my job to start a crowdfunding platform for projects that reduced greenhouse gas emissions. I started it with the hope that if I told people about the crisis, surely they would want to fund projects to avert it. I was soon to learn that hope was too naive and simplistic. Time and again I approached people to fund the projects, time and again I heard the question— “What’s in it for me?”. “Survival”, “A livable planet for your children” I used to answer. Sounds rather dramatic as I read it now, but that really was and continues to be the heart of the matter. I did not focus on the tremendous loss of beauty and wonder in the world because I thought they would consider it too soft— branding me a tree hugger, a hippie. Invariably, the reactions I got were of disbelief. Some laughed at the notion that survival was at stake. They considered what I said too outlandish and unlikely to happen or too far in the future. Others felt secure thinking that even if it did happen, it was likely to affect others and not them. Most were polite but definite in their dismissal. They thought I was asking for money for charity— a clear sign of how they considered themselves separate from the environment they lived in. About 10% of the people said they would fund the projects, but only if they could make a financial return on them. Only about 1-2% said they would be happy to fund the projects for no return as they thought it was a good cause.

This was of course in 2017 and awareness about the climate crisis is far higher now, especially in the Western world. Were I to try this today, I am sure I would find many more people willing to listen. But I share this story now to highlight some key features that remain true even today and underpin the Metacrisis:

Fear and escapism: Many problems we face today are overwhelmingly large. Confronting them invariably triggers feelings of fear and escapism, to the extent that we mostly shy away from acknowledging their true scale and scope. It is the coping mechanism of our psyches to downplay the risk because it can be hard to function in the world while accepting these harsh realities. If we truly acknowledge the catastrophic nature of the problems, we surely can’t continue our lives as though it is business as usual. The cognitive dissonance from not taking action would wreak havoc on our well-being.

Short-term bias: Since the worst effects of climate change weren’t visible/hadn’t registered with people— they wanted to continue doing things as they had always done without regard for the future. This same thinking leads to problems like financial bubbles, debt crises, plastic pollution, biodiversity loss, and more.

Fragmented/non-holistic thinking: People rightly asked “What’s in it for me?”. But they narrowly considered only financial return as a worthwhile answer to that question. A livable planet, a sustainable environment, and the beauty and joy of being in nature did not make the cut even though they are essential to human flourishing. They thought of supporting these projects as charity— without realizing that the environment will eventually be fine, it is we who will perish. This lack of systemic thinking is all pervasive— healthcare focused on treatment rather than prevention, a criminal justice system focused on punishment rather than rehabilitation, urban planning focused on cars instead of people, and more.

Primacy of money: This is a special case of fragmented thinking, but it bears repeating because a culture and economic system purely focused on maximizing financial return is a core component of what ails us today. When money becomes the primary value, other aspects of life—including health, environmental sustainability, and social cohesion—are sidelined, driving fragmentation that prevents us from solving broader crises

One can write entire essays dedicated to each of the points above. But here I will just highlight the fact that the features mentioned above are not unique to how we deal/do not deal with climate change, but are deeply ingrained in us as individuals and as a society. These strands of thinking were my first clue about the Metacrisis, though I did not know the term then. As I came to terms with these realities, I grudgingly pivoted my start-up from crowdfunding green projects to developing solar rooftop projects. Since economics seemed to be the lever that moved the world, I thought solar projects would be a good bet, a path of least resistance as they offered both clean energy and a financial return— a win-win. And so it proved for a while.

A systemic hijack

As I scaled up my development of solar projects, I began getting offers for government contracts. They were lucrative projects, that were mine for the taking as long as I was willing to part with a ‘commission’ to the middleman helping me get the project. The commission would find its way to the deciding bureaucrat I was assured—ensuring that mine would be the winning bid for the contract. I was told I could bump up the price of my bid to ensure I didn’t suffer any losses due to the commission. A win-win for me, the agent, and the bureaucracy, with the only loser being the tax-payer. Not only this, I was told I didn’t have to worry about any of this being considered illegal and finding its way back to me. Since I would never pay the bureaucrat directly, I was told that I would technically not be breaking any law and could even show the commission as a sales expense and get a tax respite. The system I was told works really well for those who know how to work it. I, however, neither knew nor wanted to learn the machinations of this system. Well-meaning friends and mentors told me I was being a fool. They said I shouldn’t mix business and charity. That I was too small to make a difference, that I should first focus on getting power/wealth and then deploying it towards solving problems I cared about. They were not wrong. And if I had started the company with profit as the primary motive, I might have been tempted to take their advice. But as such I saw buying into this system only perpetrating the kind of thinking that led us into our existential problems in the first place.

The story I tell above is not unique and could have happened to anyone in any government office anywhere across the globe. The scale and the players might change, but the core tenet is the same— the system can be hijacked for your purposes as long as you are willing to pay the right people. But why am I telling you all this? That there is corruption in the government isn’t exactly news to anyone. I share this story to illustrate the systemic nature of the Metacrisis. As my run-ins with corruption continued, I saw fossil fuel companies hijack the same corrupt system to thwart climate action. Unlike me, they had no qualms in working the system to their advantage. They perpetuated and continue to perpetuate policies that keep us locked into a trajectory of ever-increasing emissions even as 2023 ended up being the hottest year on record by far.

Big oil’s history of climate denial

How and why fossil fuel companies thwart climate policy is best understood with the example of a carbon tax — the main measure desperately needed to tackle climate change. Since the primary cause of climate change is CO2 emissions from the burning of fossil fuels, this policy proposes to ascribe a dollar value to every ton of emitted CO2 and make the companies pay for those. While there are nuances to the implementation, the net effect of such a regulation would be to shift consumption away from fossil fuels and increase the development of green energy sources. But this policy proposal hardly got any traction for decades, despite being first proposed in 1973. Why? Because threatened by the erosion of profits the world’s switch to green energy would entail, fossil fuel companies undertook a decades-long campaign to undermine climate science, sow doubt on the link between emissions & temperature increase, and elect leaders sympathetic to their cause.

The phenomenon and mechanism of climate change were first observed as far back as 1938. Using records from 147 weather stations around the world, British engineer Guy Callendar shows that temperatures had risen over the previous century. He also showed that CO2 concentrations had increased over the same period, and suggested this caused the warming. In 1965, a US President's Advisory Committee panel warned that the greenhouse effect was a matter of "real concern”. Efforts of oil companies like ExxonMobil to undermine climate science and influence policy can be traced back to almost as long. A damning chronology of Exxon’s efforts can be found in this Greenpeace report here, though Shell, BP, and Chevron were all equally culpable. A few illustrative examples include:

Scientists working for the American Petroleum Institute warned them about the causes and dangers of climate change as far back as 1968. Fossil fuel companies instead of taking action to curb emissions, shut down research into the area

Creation of panels of experts whose job was to publically claim that the role greenhouse gases played in climate change was not well understood

17 million dollars in funding to George Bush’s election campaign and the US’s subsequent withdrawal from the Kyoto Protocol which required a 5% reduction in CO2 emissions

The Greenpeace report is worth reading in full to understand how corruption undermines our ability to tackle problems where vested economic interests run counter to public well-being. These campaigns have thwarted the coordination necessary for effective action on the crisis and cost us precious decades— a delay that might ultimately prove catastrophic for the whole planet. To call what they did criminal does not begin to capture it.

Funding of political candidates sympathetic to their cause and misinformation campaigns at mind-boggling scales are unfortunately not new though. It became part of the standard industry playbook after Big Tobacco did the same to avoid anti-smoking legislation for decades until they were unmasked. Thus a reform in campaign financing is a key piece of solving the Metacrisis.

Everything is connected

The campaigns of climate change denial continue to this date and are exponentially worse in the age of social media. With social media allowing people to live in their own reality bubbles, it has become even harder to create a consensus on basic facts— a cornerstone of tackling the crisis effectively. The failure to curb fake news on social media and its knock-on effects on support for climate policy also highlights the interconnected, mutually reinforcing, and systemic nature of the Metacrisis. While it is undoubtedly challenging to moderate fake news, whistleblower accounts indicate that social media companies like Meta don’t even really want to moderate it in the first place. This is, of course, because they profit from keeping users engaged and nothing engages users more than fake news, conspiracy theories and sensational content. So they publically pay lip service to tackling the problem, while privately subverting any solution.

Social media also thwarts our ability to tackle these problems in more insidious ways. With every second of our free time being sucked in by our devices, we are now constantly distracted, increasingly depressed, and more lonely. We are either too lulled by our devices to realize that our house is on fire or too tired mentally to act on it. Meanwhile, in a move reminiscent of Big Tobacco and Big Oil, Mark Zuckerberg testified in front of a Senate Judiciary Committee that he doesn’t believe social media has a negative impact on mental health.

A problem of incentives

Putting all the pieces above together, I couldn’t help but conclude that climate change was not the real problem— it was a symptom of the problem. But what was the real problem then? I started on this journey in 2017 to tackle the issue of there being too much CO2 in the atmosphere. By 2019, I found myself thinking about corruption, policy, fake news, social media, economic systems, and political reform.

It is easy to read the above accounts of damage done by the fossil fuel and social media companies and wonder if the people running them are just evil. And while a tempting conclusion, and even possibly a part of the answer, it doesn’t get us closer to finding solutions to our crisis.

Looking at the actions of these players, we can conclude that even if not evil, they are at the least driven by greed and power. But are they unique in being that way? I do not think so. These examples stand out because of the impact the scale of these companies allows them to have. But these companies undertake these actions, because their incentive— like the incentive of all companies, is to maximize profits. We live in an economic regime where companies and their management are rewarded for growing their profit quarter-on-quarter. Since economic profit does not take into account public well-being, there really is no incentive for anyone to do things differently. Much like the folks who refused to support the green projects on my crowdfunding platform, the executives of these companies are simply asking “What’s in it for me?” and narrowly choosing to maximize economic profit because that’s what the system rewards. This system that narrowly rewards short-term economic profit is a key feature of the Metacrisis that keeps generating new crises. Big tobacco yesterday, climate change, fake news and social media induced mental illness today and AI risk tomorrow. As the late Charlie Munger wisely said— “Show me the incentives, and I will show you the outcome”.

Moloch: The invisible force behind our race to the bottom

The problem of our economic system narrowly incentivizing profits goes even further though. Not only does it not encourage anyone to take action on climate change or fake news, it actively subverts anyone who might voluntarily choose to do so. A company that actively looks at furthering public good by acting on climate change in the absence of regulation, will actually be punished by the stock market and economic system at large. If the claim seems preposterous, then a bit of game theory and an example can help clarify it.

Imagine, you are the CEO of a petroleum company— one of ten companies in the world. Also, imagine that these companies all exist in perfect competition and equilibrium— each producing crude oil at a cost of 50 dollars a barrel and selling it at 100 dollars a barrel. You being a conscientious CEO wanting to act on climate change decide to implement emission reduction projects across all your refineries. This pushes your production cost up to 80 dollars per barrel. You now face 2 choices— either absorb these additional 30 dollars in cost and reduce your profit to 20 dollars a barrel or pass on the increase to the consumers by increasing the selling price to 130 dollars a barrel.

Suppose you decide to do the former and absorb the costs. Come next quarter’s earnings calls— you tell the financial analysts on Wall Street about your wonderful action on climate change. What happens next? Are you lauded as a hero? No, the company’s stock price crashes, the competition’s stock price increases and investors and the board immediately call for your resignation. Why? Because investing in emission reduction has made your company less competitive. By reducing profits you have made it harder for the company to recruit the best talent, invest in R&D or win oil exploration rights in the most lucrative areas because all of these are a function of how much money you have available to spend. Since a company’s stock price is nothing but a reflection of how much profit it is expected to earn in the future, investors dump your stock as you have made it clear by your actions that you are going to reduce profits. The board, because of its fiduciary responsibility to safeguard shareholder value i.e. to maximize profit, must look at your actions unfavorably as well— even if they privately laud your efforts. Not quite the outcome you hoped for. As you lament your fate, thinking “No good deed goes unpunished”, you conclude that there is no way for you to act unilaterally on climate change unless all your competitors agree to do so as well.

Suppose you go the other way and decide to pass on the increase in cost to the consumers. Surely they will support you by still buying from you because they understand how big a problem climate change is? Alas, even if a consumer is well-meaning, it is unlikely to happen. Put yourself in the consumer’s shoes for a second. If you are on the highway and see one gas station offering gas for 1 dollar a litre and another for 1.3 dollars a litre— which one are you likely to choose? You want to support climate action— but you also have bills and a mortgage to pay, kids to send to school, and elderly parents to take care of. Besides, even if you were ready to pay for green gas, you think— “Most people I know aren’t going to pay for this. While I stretch my budget for the common good, my neighbors are going to continue driving their gas-guzzling SUVs. Why should I handle all this stress when the climate is going to continue to get worse because of people like them anyway? To hell with them and the world. I might as well try to save as much money as I can— who knows what tomorrow will bring.” Much like the CEO trying to absorb carbon capture pricing by reducing profits, the consumer concludes that it isn’t worth paying for green gas unless everyone does it.

Playing out this game theoretic dynamic makes it clear that there are complex forces at play here rather than people just being unwilling to do the right thing. Nobody wants climate change, not even the possibly evil CEOs of fossil fuel companies. Yet they seem unable to do anything about it without sacrificing their short-term competitiveness or survival. This system of incentives which forces everyone to compete in a race to the bottom was christened ‘Moloch’ by Scott Alexander in his seminal 2014 essay— “Meditations on Moloch”. Moloch is the Canaanite of child sacrifice (Canaan was an ancient civilization in the Middle East around 3000 BC). The Canaanites sacrificed their children to Moloch in exchange for power or favor. It was a terrible price to pay, but one the tribes paid nonetheless as the sacrifice might have made the difference between victory and defeat in war. But what if every tribe sacrificed children to Moloch? Then there would be no relative advantage for one tribe over the other, but all tribes would be left without children— eventually resulting in their own demise anyway. That then is the tyranny of Moloch— you appease it to avoid defeat for yourself, yet appeasing it leads to defeat for all. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t. This same dynamic that leads to the nuclear, AI and bio-weapons arms races is called a race to the bottom. Nobody wants to spend more on their military (it does not lead to a better quality of life) or develop these world-ending weapons. But if they don’t spend on these things, while their enemies do— then they will soundly be defeated the next time a conflict arises. So they see the abyss coming, but yet they ride towards it full throttle. They hoard 13000 nuclear weapons— enough to destroy the world dozens of times over. They try to summon the AI god, all the while making noises about how it might end the world.

A little support goes a long way. If you find this post useful, please consider a small contribution to keep this inquiry alive

Lack of an effective global coordinating mechanism

Breaking this dynamic requires either cooperation and/or a change in incentives. Let’s look at cooperation through the lens of climate change first. Suppose a country’s government has overcome all internal lobbying and corruption and decides to implement a carbon tax. Can they do so unilaterally? While riddled with many Molochian challenges, a country theoretically could go ahead with such a push alone. But it is unlikely to be of much use unless others follow suit— because we share the same atmosphere after all. Without cooperation, climate change would still continue.

But how can a country trust that others will implement a carbon tax? The institution that has tried to foster global cooperation around this issue is the United Nations. 2015 saw 196 countries sign the historic Paris Agreement at the UN climate conference. As part of the agreement, countries pledged to try to keep temperature rise limited to 1.5 degrees compared to pre-industrial revolution levels. This requires emissions to decline 43% by 2030 compared to 2010 emissions. Unfortunately, the policies countries have devised to reduce emissions are woefully inadequate— temperatures would rise 3.1 degrees by the end of the century if countries stick to them. Consequently, global temperatures have already risen by 1.3 degrees and a range of climate disasters are unfolding across the globe. And it is bound to only get worse as the gap between where our emissions are and where they need to be widens.

And consequences for countries failing to curb their emissions— none. All targets are voluntary and the United Nations has no power to enforce them. Unfortunately in the world of emissions targets— good intentions don’t work, only good mechanisms do (h/t Amazon). This issue highlights another systemic nature of the Metacrisis— our problems are now global in scope, but we have no mechanism or institution capable of coordinating effective global action. The lack of this mechanism again hurts us when it comes to the nuclear, AI, and bio-weapons race. How do we trust countries are not building nuclear weapons in bunkers or bio-weapons in labs?

The problem of equating net worth with self-worth

What about incentives? If a country’s government was more enlightened, they might chase a metric like Gross national happiness (like Bhutan) instead of a narrow metric like GDP. If the focus becomes holistic well-being, then action on climate change would automatically follow. Alas, as discussed previously, we only optimize for one thing— economic profit. But where does this desire, this incentive to maximize profits i.e. money come from? It comes from the very nature of our current monetary system. Money represents optionality. You can exchange money for anything you might consider to be of tangible value. It can be thought of as units of power (h/t Daniel Schmachtenberger) where power is defined as the ability to get what you want. The more money you have, the more you can get what you want. Built into the system is an implicit assumption that more is better i.e. the more money, the more power you have the better off you would be. Better off on what dimension exactly? That’s considered immaterial because one assumes one can always use money or power to improve life across any dimension that matters— an assumption fraught with many problems, but widely accepted nonetheless. Consequently, we live in a culture that celebrates the accumulation of wealth, where money has become our primary measure of success, of a life well lived. Forbes publishes a list of the world’s richest people, the news tracks whether Bill Gates or Elon Musk is the wealthiest person in the world today, how much Taylor Swift is set to earn from her Eras tour, how much Jeff Bezos’ new home cost— the list goes on and on. And this dynamic isn’t limited to our cultural obsession with the ultra-wealthy. When we meet people, we ask what they do and it is well understood that the only kind of doing that is being asked about is an economic one. “Oh, you are a VP at Goldman Sachs”, we say while mentally marking up our assessment of the person. As if a person can be reduced to just one dimension of being. Where you work, what you do, how much you make have all become markers of social currency and none more so than the last one. So much so that, while there are exceptions, it won’t be unfair to say that we have largely equated our net worth with our self-worth.

How did we get here

How and why did we sign up for this madness? Why do we run after power, status, wealth, and influence? The answer, at least partly, lies in our genes. We are biological creatures whose primary motivations are to survive and propagate. At the time our earliest hominid ancestors first evolved (around 2 million years ago), life was extremely hard. With the external environment being terribly harsh, having an extra hunk of meat might have meant the difference between surviving or perishing during a hard trek in a long cold winter. Being social animals, we organized into tribes with the largest share of resources going to the most powerful. Since only one person could be the most powerful, we evolved to play complex status games where we very keenly track our relative social standing. And since resources were limited, the more someone else took, the less there was left for us— a zero-sum game that led us to develop a scarcity mindset. This scarcity mindset led us to desire more and more as having more resources was directly linked to our security and propagation of our gene pool.

Fast forward 2 million years to the present— we now live in a world that is infinitely richer than that populated by our ancestors. Yet, the adaptations we deployed then to survive still remain with us— woefully out of touch with our present reality. While scarcity drove us to seek that extra hunk of meat 2 million years ago, today that same force drives us to get a third home and a second car. Since we see life as a competition, where the strongest survive— our neighbor getting a new car triggers feelings of jealousy as we feel left behind. This leads to a cycle of more and more consumption, as we try to keep up with the Joneses.

Why things are coming to a head at this moment

Now, one might rightly ask— haven’t we always competed for power, status, and resources? Why is this such a big deal now? The answer lies in a few key facts:

We are hitting planetary boundaries: We live on a planet with limited resources. Our population has grown 4X from 2 billion to 8 billion in the last century. At the same time, we have made extraordinary technological progress— leading to an exponential increase in demand for energy and natural resources. Our electricity consumption alone has grown 440 times in the last 100 years! Consequently, we have hit the carrying capacity of the planet. Earth overshoot day measures in how much time we consume all the resources (say forests and fish) that the Earth generates in a year. In 2024, the overshoot day fell on August 1. That means we had consumed a year’s worth of resources in 7 months. Where are we getting the rest from? Through overfishing and deforestation— meaning there won’t be any fish or forests left eventually! This comes at a time when 8.5% of the world’s population lives below the extreme poverty line of $2.15 a day and 44% i.e. 3.5 billion live on less than $6.85 a day! What happens to the already strained resources as their living standards and economic demands increase? Coupled with the fact our population is projected to grow by another 2.1 billion before peaking at 10.3 billion, the situation presents some very difficult constraints. How do you reconcile an economic system predicated on constant economic growth with the hard physical limits of the planet?

We now possess technology that is capable of destroying all life on the planet, many times over. And this technology is getting increasingly decentralized as in the case of AI powered development of bio-weapons. With access to such devastating technology available so easily, we can no longer afford to be operating in such adversarial systems

The world is increasingly connected: A modern car contains components sourced from 15+ countries, Apple has component suppliers in 43 countries, Russia and Ukraine exported a quarter of the world’s wheat before the conflict, Taiwan produces 60% of the world’s chips, heck even a pencil has components from 10 countries. This interconnectedness and globalization means if conflict erupts in any part of the world its repercussions are felt globally. Our just-in-time, globally connected supply chain has a lot of benefits, but resilience is not one of them.

Technology is outstripping regulation: With technological progress proving exponential, we are deploying technology faster than we can regulate it. The Molochian dynamics ensure that even with potentially dangerous tech like AI, the incentive is to get to the market first rather than test the technology thoroughly to ensure it is safe. This dynamic played out in the case of large language models. Google, the inventor of the technology, fell behind OpenAI because it wanted to play it safe while OpenAI was more willing to take the risk of releasing the tech. With regulation still woefully inadequate to regulate even more than a decade-old technology like social media, things don’t look good for us when it comes to AI regulation and safety. Short-term competitive dynamics are the last thing we should be playing into when the man considered the Godfather of AI is warning that it can wipe out humanity.

That’s a fair bit to take in, but the key takeaway from the above constraints is that the stakes are too high and we all either learn to swim together or we will sink together. Business as usual where we compete for narrow short-term self-interest is not an option.

Putting it all together

To recap what we have covered so far— we are biological creatures whose primary needs are survival and propagation. Due to the evolutionary pressure of a harsh environment, we evolved to seek power, status, and more resources as that increased the likelihood of propagating our gene pool. Over time, these adaptations/strategies remained with us even as we built economic and social systems that improved our material conditions well past the point of needing to worry about survival. However, these systems also exacerbate our tendency to think short-term and non-holistically, incentivizing us to play zero-sum games, while sacrificing our holistic well-being. With technology and population growth leading us to hit planetary boundaries, these economic and social systems that have worked for us till now are proving detrimental. The problem is further exacerbated by the interconnected nature of today’s world— while many of the problems we face require global solutions, we lack any effective coordination mechanism to implement them. And we are too blinded, too caught up in the system to see it all clearly or act decisively even if we do.

Not all doom and gloom

So where does this leave us? Reading everything above, you might conclude that I have a very grim view of capitalism, the tech industry, fossil fuels, human nature or the future of the human race. You might also think I am advocating for throwing out the whole system wholesale. But that is not the case. Fossil fuels, putting aside their unfortunate effect of ecological breakdown for a moment, have been the main drivers of our civilizational growth. To put things into perspective, each barrel of oil roughly provides energy equal to 4.5 years of human labor. In 2023, we collectively consumed energy equal to about 84 billion barrels of oil from coal, oil, and natural gas. This means we effectively have 378 billion fossil slaves working for us 24x7. Those are staggering numbers. The lifestyles we enjoy today simply would not be possible today without fossil fuels. Our dependence on them means that there is no easy solution where we can switch away from them completely tomorrow or even in the next decade or two. In fact, were we to try to stop using fossil fuels tomorrow, it would probably trigger World War 3 as countries would invade each other to maintain their standard of living.

Similarly, capitalism for all its flaws, has created a global engine that has led to massive increases in prosperity on many dimensions. It has spurred innovation and productivity and led to the development of new technologies that have transformed healthcare, communications, transportation, and more. This improvement in material conditions has also contributed to longer life expectancy and better quality of life.

When it comes to human nature, while I have focused above on our tendency to be short-term, non-holistic thinkers competing for power and status, I also know that we possess the ability to cooperate, empathize, innovate, love, and be courageous, kind & wise. The development of the Covid vaccine in record time through unprecedented global cooperation, the moon landing, the ending of slavery, the progress of civil rights, the formation of the United Nations, the eradication of Polio, the international cooperation to rescue the 12 children trapped in a cave in Thailand, the life and legacy of Helen Keller, the courage of Oskar Schindler— I can go on and on with examples that show the triumph of the human spirit. The fact that I can sit here today and write these words on a contraption made of what was once sand, dinosaur flesh, and rocks and beam them to you across the globe via satellites flying hundreds of miles high in space and thousands of miles of cable underneath the sea is testament to the fact that we humans can achieve great things when we come together. In fact, there wouldn’t be much point in writing this essay if we couldn’t. It would be a tremendous waste of time, both mine and yours, if the gist of what I wanted to say in 8000 words is “We are all doomed”. We aren’t, not yet anyway. Our situation is grim, but not unsalvageable. But salvaging it and ensuring that we not only survive but thrive will demand the best of us and then some more. It will require us to tap into goodness, beauty, truth, wisdom, compassion, and all that makes life worth living. (h/t Daniel Schmachtenberger)

The way ahead

We face a crisis that is unprecedented in its scale and complexity but it is also an opportunity for great transformation. My first foray into solving climate change ended with the shutdown of my start-up in the middle of Covid in 2021. What I learned during my 3.5-year journey convinced me that we need a spiritual revolution to address the problems we face. I know that might sound a bit woo-woo, so allow me to elaborate. To me, spirituality is a quest to understand life’s meaning and purpose and live in accordance with them. Our values, defined as our standards of behavior or things we consider important in life, derive from what we believe gives life meaning and purpose. And the systems and societies we build are ultimately downstream of the values we hold. Most people chasing power and status, are ultimately driven by insecurities and a fear of death. They hold misguided beliefs that life is a competition and success is measured by one’s ability to achieve more than others, by leaving a legacy or other such trappings of the ego. It’s the kind of thinking that has landed us in the soup we are in. In an alternate framework, one might believe that what gives life meaning is living in harmony with ourselves, other people, and the environment. If more people subscribed to this belief system, many more countries would have constitutionally protected forests and focus on gross national happiness like Bhutan. Shifting to this framework requires that instead of being driven by our fears and insecurities, we deeply start asking ourselves “What truly makes life worth living?”

This shift isn’t impossible. The overbearing influence that wealth has today didn’t always reign supreme. In his brilliant 1831 essay ‘The spirit of the age’, John Stuart Mill, a British MP and deeply influential philosopher, stated that there are three sources of moral influence in the world— religion, eminent wisdom & virtue, and worldly power (wealth, nobility, political). He goes on to state that in stable and natural states of society wisdom and virtue coincide with worldly power. It is only in an age of transition, like ours, where wisdom and worldly power have gone separate ways. Of course, social media has had no small role to play in this. But it’s important to note that for all the challenges this time presents, it remains transitory. Sooner or later things must reach a stable equilibrium.

But reaching this equilibrium requires us all to come together. It will require us to change education to focus on developing wisdom, character, and long-term, holistic, systemic thinking instead of getting a job. It will require us to reimagine our economic system to make it compatible with our planetary boundaries, devise ways to avoid regulatory capture, change our cultural narratives and more.

Reasons for hope

These are not easy problems and they won’t have silver bullet solutions. Solving them will require an audacity of hope and imagination. Luckily, we have those in plenty. In one of his most powerful interviews, Steve Jobs said— “Everything around you that you call ‘life’ was made up by people who were no smarter than you. And you can change it, you can influence it, you can build your own things that other people can use.”

If the task of global coordination seems daunting, then realize that even the concept of countries, something that we just assume as a basic fact of life, didn’t take shape until the 17th century. Already people are reimagining this concept for a digitally connected 21st century by trying to create network states.

If the task of reshaping education seems overwhelming— then realize that it can be achieved through AI tutors that can allow anyone in the world access to personalized education that was once only available to nobility.

If the planetary boundaries and our emissions seem concerning, then realize that the cost of solar has fallen 90% in the last decade and renewables are the fastest growing energy source. Not to mention that a breakthrough in nuclear energy or superconducting can completely change the planetary boundaries equation, providing us virtually limitless emissions-free energy.

If transforming our economic system and stopping regulatory capture seem impossible, then remember the Civil Rights Movement that ended centuries of racial discrimination.

If curbing our drive for power and status seems like a pipe dream, then look towards meditation practices like Vipassana that successfully allow us to do so. Realize too that what part of human nature we express— the competitive or cooperative, can be shaped by our culture and incentives (h/t Daniel Schmachtenberger).

If implementing a carbon tax seems impossible then look to Europe’s carbon border adjustment mechanism that’s set to start in 2026.

The solutions are out there, we only have to show the will to make a change.

What you can do

If we seize the moment, not only can we survive but we can also create a significantly brighter future for us and all the species inhabiting this planet. But this is not a change that can be driven by a few individuals or even a few countries. It will take us all asking ourselves who we want to be, whether we will display the courage necessary to face this peril or will we watch passively as everything we hold dear hurtles into the abyss. We have reasons for hope, but we are still woefully behind all that we need to do.

If what you have read so far resonates with you and are wondering what you can do, then consider taking the following steps:

Educate Yourself: Follow leading Metacrisis thinkers like Daniel Schmachtenberger and Nate Hagens . Awareness and understanding are the first steps toward transformation. Educating ourselves about the complexity at play here is the first step we can take to make a difference Else any solution we propose will succumb to the same fragmented, non-holistic thinking that has led us into this predicament in the first place. .

Support Systemic Action: Vote for leaders who prioritize climate action, economic reforms, and systemic solutions. Use your influence to advocate for campaign finance reform, better climate policies, and educational changes.

Join the Conversation: Share your thoughts in the comments, connect with others who are passionate about systemic change or simply start conversations within your community. The more we understand and discuss the Metacrisis, the stronger our collective response will be. If you'd like to join me in exploring these ideas further, subscribe to this newsletter or email me at akhilpuri@substack.com. I’ll continue diving into the causes of and solutions to the Metacrisis. Together, we can build a movement that challenges the status quo.

Leverage social media: Follow and amplify voices working towards solutions, share educational content, and challenge narratives that reinforce short-term thinking. Used right, we can turn social media from a foe into a powerful ally in shifting cultural consciousness

At its core, the Metacrisis thesis indicates that everything is connected- not just for our problems, but also our solutions. This essay focussed on the Metacrisis through the lens of climate change. Equally complex essays can be written about our myriad other issues and looking at them in isolation can seem overwhelming. But once we get to the root, we see that similar patterns generate all our problems and that’s when solving them suddenly seems possible.

To anyone already working on the challenges of our times, I hope this essay serves as an invitation to think more systemically. To those who feel our general malaise, are overwhelmed by our myriad problems, and sense that something has to change—I hope this essay tells you that you are not alone and serves as a call to action. The moment is ripe for a new way of being to come into existence. I leave you with this video from the peerless Carl Sagan that encapsulates everything I have written here. Our future hangs in the balance and you are needed.

Alternatively, if you find this post useful, please consider a small one-time contribution to keep this inquiry going

Special thanks to Nidhi, David, Vivek, Tarun, Liam, Catarina, Sarath, Aarushi and Salonika for comments on early drafts of this essay

Akhil, Great essay! This is the first thing I've ever read from you. Lots of great info and perspective on the Metacrisis. I saved several statements from your writing that I thought were fantastic.

So now a gentle critique. Where would you say you fall on the Ladder of Awareness as explained by Paul Chefurka? It can be found here: http://www.paulchefurka.ca/LadderOfAwareness.html

I was a bit perplexed by your comment "a breakthrough in nuclear energy or superconducting can completely change the planetary boundaries equation, providing us virtually limitless emissions-free energy." Do you really believe that? Even if we accomplished those breakthroughs, do you think that would change anything?

Thank you for sharing your wisdom! Keep up the great work!

Very well put points. Very thought provoking. Definitely need more detailed thought process on the sub topics to spread awareness